Tianjin 1988: A Winter's Journey Through Chinese New Year

Also, riding side saddle with a student through the snow

Image courtesy of chineseposters.net

I was 26 years old when I went to Beijing to teach in 1987. I wrote prodigiously at the time, filling notebooks and composing travel essays about the cities I visited. Today, to mark the Lunar New Year, I’m sharing an essay I wrote in 1988 after a short trip to the city of Tianjin.

First a remark about my students at Beijing Foreign Studies University. They were older than me and were already established in the jobs. Their year in the capital city to improve their English was usually preparation for further study abroad. In the winter of 1988, I visited students in Tianjin, a short train trip east of Beijing.

The original essay was typed on 11 sheets of A4.

I’ve redacted it for clarity and brevity. Some of my observations now feel out of place with the wisdom of years.

China has prospered enormously over the past three decades. When I wrote this, a refrigerator and colour TV were signs of success; today urban apartments are lavishly and stylishly outfitted. Dating rituals have changed and hardly anyone rides a bicycle anymore so what I called in 1988 the “living image of romance” - a boy riding a bike with his girlfriend sitting side saddle on the bike rack - is also out of date.

Kiesslings restaurant is still around.

Sadly, I have lost all contact with the students mentioned.

Thank you for reading. I appreciate your comments.

The Market

The two characters that form the name of this city have a narcotic effect when one hears them pronounced again and again, in the clear ringing tones of Mandarin Chinese. Tianjin. The name becomes as beautiful as its meaning, the characters word-images for that which they represent. Tian: heaven, sky. Jin: ford or ferry crossing. Together: A place where the sky comes down to touch the traveller, a passage to heaven. Tianjin.

In the market, northern Han austerity gives way to the conviviality of the Chinese New Year as fireworks, firecrackers, sparklers and red paper cuts exchange hands like bets before races. The burning red schoolhouse of my childhood is not among the selection. It has been replaced — appropriately — by a pagoda. A feeling of tremendous relaxation comes over me in Chinese markets, a feeling of reassurance, for I am bonded to the other market-goers by a common wish — for the freshest fish and vegetables, the juiciest melon, the best bargain. We are connected by the shared joys of bargaining and eating.

Wrinkled hogs’ heads on the butcher’s table; a Strauss symphony trumpeting from inside the barbershop; chickens, their legs tied together, hanging from the handlebars of a bicycle; staring children. What I see and what I hear is the stuff of haikus, absurd juxtapositions, like the very spirit of China itself, a contradiction of foul and fragrant.

I make faces at the children, mock-scary faces. To one who is riding piggyback on his father, I practice my limited routine, a formula for success.

“How old are you?” I ask. “Really? So big? What’s your name?” Like all children, they need prompting from their parents, especially when faced with a yellow-haired alien, a foreign giant with albino eyes. Proud that his little emperor has caught the attention of the foreign auntie, the father answers for his shy boy.

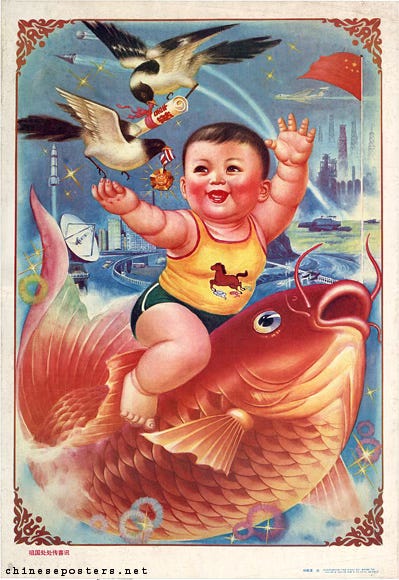

There are paper lanterns and the ubiquitous fat-baby-on-flying-fish posters for sale in the market. I buy plump dried apricots the way we used to buy French fries, in a paper cone. I buy toothpaste and a tiny tin of hand cream and for fun a matching cardboard container, the size of a mini hatbox, of what I assume is face powder. The two are a set, decorated with a pink, green and black floral pattern, like a set of doll dishes.

It begins to snow, heavy, wet flakes and as I walk back to the university where the radiators snort and belch, but where it will be very warm, the commuters on their bicycles are wearily peddling the wet streets, in the darkening evening, through the oncoming snow.

The Guesthouse

At Tianjin University where I have bargained for a room in the guesthouse, the windows are industrial-sized like the ones in the tech wing of my high school. The notice at the reception desk announces generous hot water services, from 7-9 am, 11-2pm, and 6-11pm. It fails to mention that hot means boiling hot and that both hot and cold water come from the same tap. In other words, there is either boiling hot or cold water, but never both at the same time.

A plastic sign hanging from the doorknob says “Please do not disturb” on one side and “Please arrange the room right now” on the other. I drink instant coffee from one of the packets of European Blends given to me by a Californian friend in Beijing. Choosing Cafe Viennese (“a taste loved in Vienna where sophistication and fine taste are a way of life”) and mixing it with hot water from the ever-present thermos, I relax in the armchair with white crocheted antimacassars.

My Host

It is cold and damp as Zhao Li Juan and I trudge through the snowfall. She has invited me to her home for dinner where she and her husband make jiaozi, a simple, traditional dumpling stuffed with ground pork and finely chopped greens, boiled and eaten with a sauce of soya and malt vinegar. They have a single child, Ting Ting, a beautiful daughter with big black eyes, carmine lips, and a boyish haircut. Ting Ting’s mother is one of the brightest students I had in the intensive English course at the university in Beijing. She speaks impeccable English, studied mechanical engineering, and has won a scholarship to do research at an institute in Sweden.

Their flat is three small rooms, including the entrance area where we eat. It is uncomfortably cold and damp, due to the concrete floors and feeble heating. Although I am wearing long underwear, corduroys, a long sleeved undershirt, three sweaters, heavy socks and boots, I am freezing.

Xiao Jar, the nickname given to Zhao Li Juan by her classmates, means “Little Engine” because she is always on the go and never gets tired. She takes me shopping, because as any Tianjinese will tell you, the selection, variety and price of goods are all superior to what can be had in snobby, overpriced Beijing. She takes me to “Clothing Street” where the shops are full of embroidered and beaded sweaters for winter, and long wool skirts, wide enough to wear on a bike but smart enough to wear for a night out.

The City

“Old Culture Street” is a makeover of the past. It is one narrow lane with emporiums and shops renovated in the old style, with cake trim on the roofs, enormous red lanterns hanging in generous archways, small-paned windows and the characteristic rust red paint. The shops are overflowing with fireworks and firecrackers for the approaching Chinese New Year. Shops selling antique style silk robes cater to old people who want to be buried in traditional clothes. Toy shops entice little emperors and empresses who tug at their parents’ sleeves. “C’an c’an,” they beg. “Look! Look!” For them it is Christmas, a time for round-the-clock feasting, staying up late, days of non-stop fireworks, a month long holiday from school, new clothes, new toys, and gifts of money presented in red envelops.

Little Engine often asks for directions of people locked in bicycle jams with us while waiting for the traffic light to change. (“Eh, tong’zhi” she calls softly, “hey, comrade”). She asks an elderly man steering a tricycle, a small trailer attached to the back loaded with cleanly picked bones.

We stop to rest at a café located above a trinket shop. The waiter is asleep in a barber’s chair. Under the glass counter is the menu, live: Cans of Coke, Sprite, and Fanta, dry cookies, a jar of Nescafe. We order Nescafe, pay the man and enter the cafe. Although the northern winter sun outside is strong and bright, the cafe is dark and dingy, as if it hadn’t been aired after a long smoky night. When I open the heavy drapes to let in the light, the couple revealed to be necking in a booth on the other side of the small room object. We are the only other patrons. The young man chain smokes, holding his girl protectively around the shoulder with his free arm.

In “Food Street” we sit down for lunch in a fancy modern seafood restaurant. At a big table eight businessmen are enjoying the end of their lunch. The Westerner among them, most certainly the guest, looks confused as his colleagues dive into each new dish as it arrives from the kitchen, polish off a few helpings, and offer another round of Marlboros.

Little Engine insists on paying for lunch although we stage a protracted battle to cover our embarrassment, me snatching her wallet and she grabbing it back. Two plates of seafood cost 24 yuan, a wildly expensive lunch and for her, perhaps a quarter of her monthly salary. When she comes to my country, she says, she will be my guest and I can invite her. I buy fireworks for Ting Ting. The etiquette of giving and receiving in this context, of both strong obligation yet sincere generosity, is scary and mysterious for me.

I wake at 8am the next day and bluster, puffy-eyed, through the door of the Dining Hall of the guesthouse minutes later. Breakfast? The dreaded word is pronounced. “Mei-you.” None left. At a roadside stand I get an egg crepe with a deep-fried doughnut twist, onion and hot sauce, made on the spot and piping hot for about 15 cents. Back at the guesthouse I spoil myself with Double Dutch (“inspired by the Dutch who are famous for making rich, irresistible chocolate. Truly indulgent”). Then I am out of European Blends.

The foreign concessions — a peculiarity of coastal cities in China — are noticeable now only by the once grand but now decrepit houses and bank buildings. The British, French, Italians, Germans, Belgians, Japanese and Russians all wanted a piece of the lucrative pie that was Tianjin’s trading port during the second half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th. Strategically and commercially important as a port town, Tianjin was topped only in grandeur and significance by Shanghai and in political importance only by dull but powerful Beijing. On Jiejang Road stand the European banks, post and telegraph offices, and printing house, one with Roman columns, another with the date 1900 cut in stone above the entrance. Little Engine’s husband was raised in a villa in the Italian concession, but didn’t enjoy it. His family eventually moved into a modern apartment block because they found heating the high ceilinged rooms in the villa expensive and wasteful.

Little Engine takes me to Kiesslings, an Austrian patisserie. Located in the town center, Kiesslings is an institution, famous with backpackers as a place to reactivate the sugar tastebuds. Inside, the café has an upper level balcony shaped like a racetrack with long fringes of glass beading hanging from it. Little Engine worked here during the Cultural Revolution and says it was a refuge from the madness of the time. The work wasn’t hard, they were warm, had enough to eat, and weren’t “sent up to the country” like many of their classmates. Little Engine takes the opportunity to call on an old friend from that time, who is loud, proud, and talkative. Her hair is done in the latest style, a pin curl perm, teased high away from her forehead. She tries to convince Little Engine to get a perm too. Her daughter is a child TV star — “all the kids in Tianjin know her, she’s got a terrific voice”, she boasts and I imagine her to be one of the wind-up dollies I’ve seen on television, with red hair ribbons and dots of rouge and bright lipstick, singing traditional folk songs. She asks Little Engine how old I am, and then, like rapid fire, asks everything else she wants to know about me: Nationality? Income? Married? Kids? Husband’s income? She explains how Little Engine was always the bright one, always ambitious, always wanting to study. Now she’s going to Sweden. The friend with the child TV star doesn’t seem at all envious. She’s a righteous Tianjinese and involves me in a one-sided conversation about the merits of Tianjin over Beijing — the people aren’t snobby, the food is better, the prices aren’t outrageous.

Riding Side-Saddle

That evening Little Engine and her classmates from Tianjin have organised to cook dinner in honour of their teacher’s visit to their hometown. Dr. Zhao, Dr. Wang, and Teacher Li all join the festivities. Dr. Zhao is a lovely young man, with a beautiful broad face. He wants to go to Toronto to study, asks my advice, and keeps refilling my glass with beer before it is empty, to help keep the promises flowing, which they do. The more he drinks, the more he talks, admitting first that he has a girlfriend, then that he doesn’t want to marry her and then that he might like a Westerner for a wife. The others are titillated by his scandalous secrets. We break up the party early and Dr. Zhao insist on taking me home on the back of his bike. It is a cold night but bright from the light of a full moon. Many couples are double riding, the girls sitting side saddle on the carrier rack, hugging their boys close around the waist. Double riding is the living image of romance in China, the girl leaning her weary head on her boy’s back, the boy physically protecting her from the dust, cold, and wind. In fact, so strong are the connotations that double riding is as good as a public announcement of impending marriage.

Dr. Wang chaperones us on his bike. As we head down a narrow alley, a truck approaches us and Dr. Zhao says, “Don’t worry, I can manage.” Somewhat prudishly I am holding on to the underside of the bicycle seat and after a time he says, “You can hang on to me.” I place my hands on his hips where I can feel him peddling hard and fast, his legs moving up and down, up and down. There is an adolescent thrill to this trip, him taking me home in the clear, still, bracing winter night and I sense that the feeling is not lost on him. “I’ll carry you up,” he jokes as we arrive at my guesthouse, and secretly, I wish he would.

What a rich collection of experiences! If you had not kept a journal do you think you would remember all of these experiences? And if so, would you recall them exactly as you wrote them back then? You have included so many vivid details I feel I can envision each scenario. Thanks for sharing. - Julie

Gorgeous! So evocative. Wish you would write that book of travel essays.